Legal Framework On Cyber-Violence Against Woman: Challenges And Road Ahead

The Indian and International Legal framework on Cyber-Violence against Women and the challenges involved in the implementation of gender-specific laws brings forth the original nature of protection available to women in this digital epoch. This article attempts to critically analyse the momentum of the Indian and the International Legal framework on cyber-violence against women. The authors, through an… Read More »

The Indian and International Legal framework on Cyber-Violence against Women and the challenges involved in the implementation of gender-specific laws brings forth the original nature of protection available to women in this digital epoch.

This article attempts to critically analyse the momentum of the Indian and the International Legal framework on cyber-violence against women. The authors, through an empirical study, surveyed the instant issue, at a considerable scale, to comprehend the awareness of it amongst people from all spheres.

The survey performed through the Google Form received a notable 103 responses. An analysis of it reveals the objective as well as the subjective answers of the people, which will be, gradually, discussed in the article.

Introduction

The widespread use of computers increased from the early 1970s, and its integration with the information and communication technologies (hereinafter referred to as ICTs) through the internet established a unique platform of cyberspace.[1] Not only are the activities new but also the violence that spreads through it, such as the persistent and the emerging nature of cyber-violence against women, also called online gender-based violence (hereinafter referred to as GBV).

The Association for Progressive Communications, a network of non-profit organisations, defined cyber-violence against women as an act of gender-based violence (hereinafter referred to as GBV) ‘committed, abetted or aggravated’ in part or whole by the use of ICTs. Cyber-violence against women infringes their right to self-determination, ability to mould their identities online, engage in socio-political etc. interactions.[2]

Feminist jurisprudence has consistently been an advocate of the theory of “special rights” of the women. It aims at investigating the gendering of the world and identifies various disadvantages faced by women.[3] It per se affirms GBV as incipient and infinite. In light of this, Catherine Mackinnon, an American radical feminist on feminist account of law, has persistently been advocating to formulate women-specific law and reform the neutrality of the law.[4]

In India, there are around 640 million[5] internet users presently, which is four times the number of users in the year 2015. Looking at the trend presently and after the COVID-19 outbreak, internet users are expected to increase in the future as people worldwide are resorting to the internet as their source of entertainment and livelihood.

According to the National Crime Records Bureau, there were around 21,700 cases[6] registered on cyber-violence in India, which was a 70% rise in the cases as compared to the previous year. If that is the trend, the escalation in cyber-violence, particularly against women in the year 2020, after the imposition of complete lockdown in the light of COVID-19 is expected to increase.

It is noteworthy that research suggests that 73% of women worldwide have experienced some form of cyber-violence in their lifetime.[7] Under the international legal framework, a gradual attempt is noticeable in addressing the same, but there is a narrative gap in the sense that a centralised focus is required.

The relevance of this also emerges from the viewpoint that COVID-19 pandemic will ultimately see a gradual increase in the use of ICTs, and a centralised mechanism is needed reminding that cyber-violence is boundless.

I. Indian Legal Framework on Cyber-Violence against Women

In today’s era, Internet finds an imperative and indispensable position in our lives and has been recognized as a Human Right by the United Nations Human Rights Council in the year 2016,[8] where its role has been considered instrumental in exercising various other incidental and ancillary rights e.g. the right to freedom of speech and expression, which is considered to be one of the founding stones or Magna Carta of various other Human Rights.

All the criticisms about its recognition as a Human Right have been invalidated and nullified after COVID-19 pandemic hit the world and restricted physical movements. In short, the world depends today on the Internet and there is no doubt about the same.

But the niggling and vexatious issue here is whether India is ready to heavily rely on the blatant use of the internet, i.e., are we efficient enough to deal with the menace, which may be caused in the virtual world against women in the form of cyber-violence?

To begin with, there is no single legislation to address the issue about cyber-violence against women for the reason that there are many overlapping and grey areas, which are covered, simultaneously, by various statutes, i.e., Indian Penal Code, 1860 (hereinafter referred to as IPC)[9] and the Information Technology Act, 2000 (hereinafter referred to as IT Act).[10]

However, before scrutinizing the laws about cyber-violence, it is incumbent to understand, in brief, its types and the forms in which, it is prevalent in today’s time in India:

- Stalking– It is one of the most common ways of harassment in the cyberspace, where a person is closely followed by another for any purpose (not being bona fide) and meddling with the privacy of the victim by the way of flooding their inbox with unnecessary messages or e-mails etc.

- Pornography– The Cambridge Dictionary defines pornography as acts, which are devoid of any creative significance, made to show sexual acts.[11] This poses as one of the most prevalent threats to women in India and the world writ large for the reason that morphing, which is another form of cyber-violence and a sub-category of pornography, uses doctored pictures (facial pictures) of women and superimpose them on those engaged in sexual acts, which is one of the biggest intimidations to the uprightness of women.

- Defamation– It is another serious menace, which has harrowing consequences on the victim. It includes bullying, publishing ill about the victim on virtual mediums, hacking the victim’s account or creating a fake I.D. to publish or post ill about some other person.

- Online Harassment- Cyber-violence is an act of crime, which is done with the use of computers or phone or any electronic device as the primary medium.[12] Thus, it also incorporates within its domain, online harassment, where the victim is continuously bombarded with unwanted messages or e-mails etc.

The reasons for not limiting laws against cyber-violence against women to a single statute are prima facie that Internet cannot be said to be limited to a particular geographical space or boundaries, i.e., its spread is universal[13] and it also gives complete autonomy in the form of unrecognised and concealment of identity to the user, which makes it a dangerous place for the reason that anyone sitting in any part of the world may commit any crime.[14]

Thus, to avoid any issues about jurisdiction and the applicability of the particular Act, both IPC[15] and IT Act[16] may be attracted for their territorial application thereof. Whereas IPC is a general law, the IT Act is a special law and when there is a conflict between the two, the maxim generalia specialibus non derogant can be invoked and taken resort to for establishing the supremacy of special law against general law.

The same was upheld n the case of S. B. Digumarti v. Govt. of NCT of Delhi.[17] IT Act, under s. 77 A, directs that no offence, which is committed against any woman, is compoundable under the said Act.

A. Provisions under the Information Technology Act, 2000

Chapter XI of the IT Act has been enacted to give effect to various punishments about cyber-crimes and thus, there are certain safeguards available to women in the form of these provisions.

- 65 deals with the issue of tampering with the offence of tampering with computer documents and attracts a punishment up to three years or fine or both.

- 66 deals with computer-related offences and attract a punishment up to three years or fine or both.

- 66C deals with punishment the offence of stealing identity and attracts a punishment up to three years or fine or both.

- 66E deals with infringement of privacy and states that if the accused is found intentionally capturing, transmitting or publishing the image of a private area, without her consent, shall be punished with a term up to three years or fine or both.

- 67 deals with the offence of transmitting or publishing obscene material online attract punishment for a term of three years for the first offence and fine, which shall extend to five years and fine for subsequent time.

- 67A deals with the offence of transmitting or publishing material about the act, which is sexually explicit and attracts a punishment for a term of three years for the first offence and fine, which shall extend to five years and fine for subsequent time.

B. Provisions under Indian Penal Code, 1860

- 292 is a corollary to s. 67 of the IT Act and deals with those who the exhibition or sale of obscene material, which attracts a punishment up to two years and fine for the first time and a punishment up to five years and fine for the subsequent time.

- 509 provides for punishment in case any word, gesture or act is committed with an intention to hurt the modesty of a woman and attracts a punishment up to three years and fine.

- 354D was added by the way of amendment in the year 2013 and attracts punishment for the accused, if he monitors the use of the internet, e-mails or any other electronic mode of communication by a woman, up to three years and fine for the first time, which may extend to five years and fine for the subsequent times.

C. Landmark Judgments on Cyber-violence against women in India

(i). The case of Yogesh Prabhu v. State of Maharashtra[18] was the first case, where the accused was punished for the offence of cyber-stalking on the complaint of cyber cell.

The facts of the case depict a clear scenario of stalking, where a lady, who used to chat with the accused on a friendly basis, turned down the proposal of the accused, which later resulted in stalking and thereby leading to the victim making a complaint to the cyber cell, where the accused was convicted under s. 509 of the IPC read with s. 66E of the IT Act.

(ii). The case of S. Katti v. State of T.N.[19] is another glaring one, which marks its presence as the first conviction in the offence on pornography, where the Court convicted the accused under ss. 469 and 509 of IPC read with s. 67 of the IT Act.

The facts of the case stated a situation, where the victim was continuously being harassed by the accused after she had turned down his proposal. The victim found out that a fake e-mail had been created in her name, by the accused, with her details being publically posted, which attracted a lot of problems leading to complaints against the accused, which led to his conviction after the trial.

(iii). In the case of Avnish Bajaj v. State,[20] a landmark judgment authored by S. Muralidhar, J., which upheld the liability of the third party on the virtual medium and quoted that there is an incumbent need for coming up with a legislative framework to preventing the dissemination of pornographic materials on the internet.

II. Status of the International Legal Framework on Cyber-Violence against Women

Cyber-violence is an act unrestricted by geographic and political boundaries. Therefore, the understanding of the legal framework on it, at the international level, is of utmost importance.

In the prominent case of Cotton Field v. Mexico,[21] the Inter-American Court of Human Rights extended the jurisprudence on violence against women. It was for the first time that States’ due diligence and obligations on the issue was accepted.

This case further expanded the vision of the States worldwide in addressing violence against women. It highlighted the ineffectiveness of the States in decreasing the level of impunity faced by women.

A. Momentum of International Accountability

(i). In 2006, the Secretary-General’s in-depth study on all forms of violence against women[22] highlighted the unacceptability of forms of violence against women around the world. It identified the need for an inquiry about the use of online ICT platforms which are contributing to the expanding horizon of violence against women and take actions to acknowledge and address them.

(ii). In 2011, the Report of the Special Rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression[23] identified the application of international human rights law to cyberspace which has eventually become a unique platform for the exercise of the right to freedom of speech and expression.

(iii). In 2012, a resolution was adopted by the Human Rights Council on the promotion, protection and enjoyment of human rights on the Internet.[24] It reaffirmed the need to protect the online rights of the people similar to what they have in person, in particular, the freedom of expression embodied under the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

(iv). In 2013, the Report of the Working Group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and practice[25] acknowledged the existence of diverse forms of cyber-violence against women which hinders their ability to engage in socio-economic discussions and debates.

The Commission on the Status of Women produced its conclusions on the elimination and prevention of all form of violence against women and girls[26] acknowledging the need to combat cyber-violence caused through ICTs.

(v). In 2015, the Report of the Special Rapporteur on violence against women acknowledged cyber-stalking and cyber-bulling to fall under the acts of domestic violence. It aggravated the momentum of identifying the extent of cyber-violence against women.[27]

Further, the final report of the Broadband Commission Working Group on Gender[28] recommended the practice of sensitization, safeguard and sanctions to combat cyber-violence against women and girls.

(vi). In 2016, The United Nations General Assembly adopted a resolution identifying the right to privacy in the digital age. [29]

(vii). In 2017, the Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights on ways to bridge the gender digital divide from a human rights perspective[30] highlighted the need to formulate legislation and take appropriate measures, such as investigation of instances of cyber-violence; response to perpetrators; reparations to the victim, etc., to tackle cyber-violence against women.

All must comply with the international human rights rules and standards, including the restrictions placed on the freedom of speech and expressions under Article 19(3) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Prevent, React, Redress approach is adopted to tackle the issue. These momentums further reflected in the General Recommendations of the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW).[31]

(viii). Recently, in 2018, the Report of the Special Rapporteur on Violence against Women[32] identified the need to eliminate cyber-violence based on gender for the new generations who are prone to these unique platforms.

B. Call for a New Convention: Challenges and Road Ahead

To end various forms of GBV is a part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. As cyberspace has existed for a short time, there is a narrative gap under the international legal framework to address this issue.

A new convention could be helpful because cyber-violence is transboundary, but this would bring advantages and challenges both which are as follows:

Advantages

The present international legal framework does not explicitly address the issue of cyber-violence against women; hence a new convention will holistically acknowledge the varied forms of it. It will present an understanding of the acts that can comprehensively be defined as cyber-violence.

It will produce a detailed approach for the states in executing due diligence obligations and make necessary amendments in their national legislations. It will present a robust response mechanism, procedure and remedies for the ICTs to follow.

It will also be a new tool for activism and socio-legal change aiming at creating safer platforms. Lastly, it will accompany the existing international human right laws.

Challenges

A specific convention on cyber-violence against women might undermine the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women. The states might show their reservations regarding the holistic definition of cyber-violence.

It might result in the repetition of similar ideas, contexts and procedures, along with excess transaction costs and diversion of resources. Amending might be an issue where the aspects of violence evolve with time. Cyber-violence is viewed as a private matter for the states, and the uncertainty about the exact global level of it fails to garner attention on the issue under public international law.

Conclusion

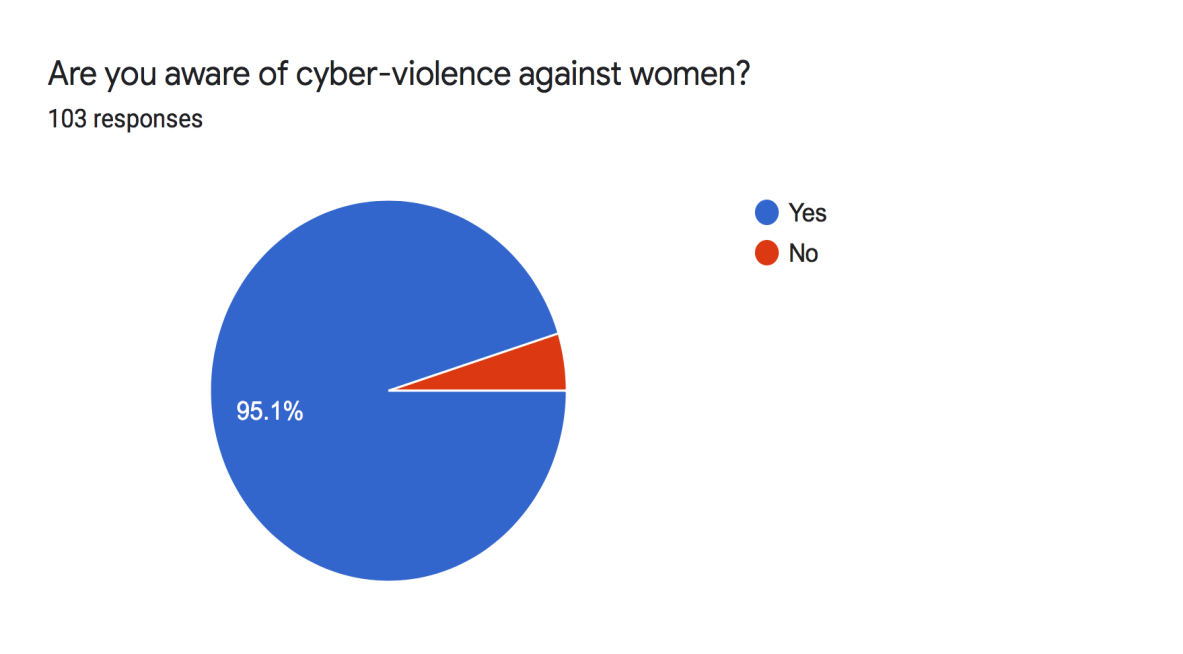

In an empirical study, which was conducted by the authors, in the form of a survey, comprising of eight questions on cyber-violence against women in India, 95.1% people accepted the fact that they are aware of the menace of cyber-violence, which has been depicted in Fig. 1.

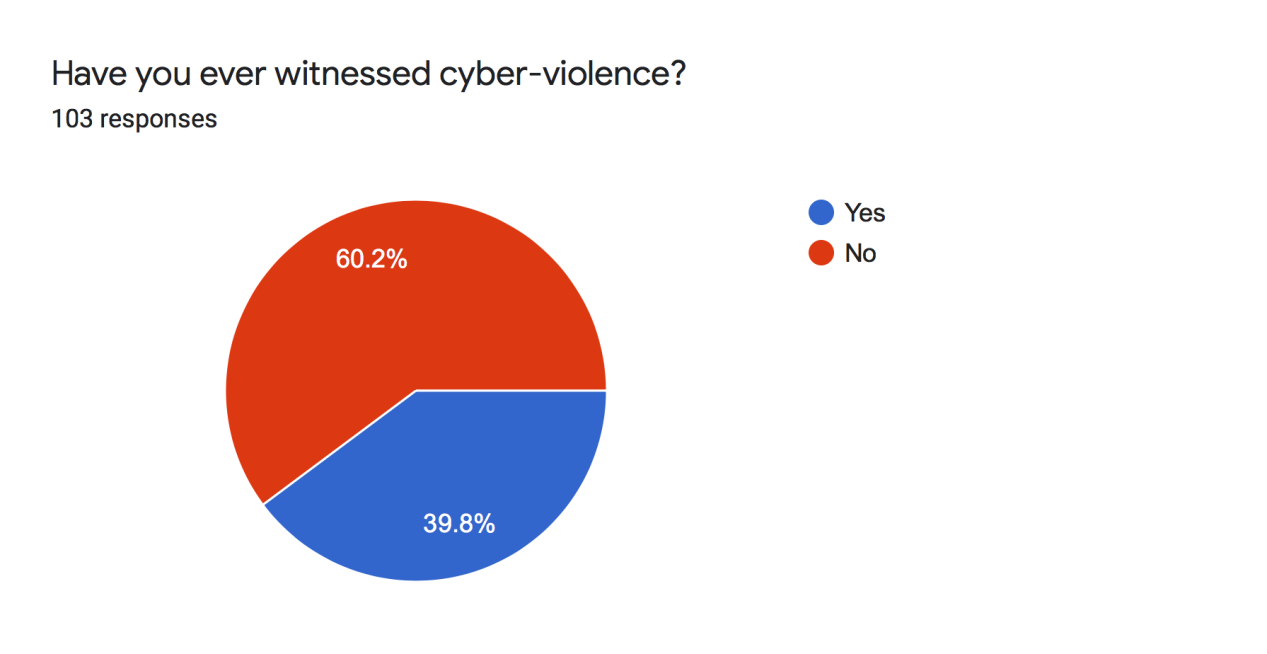

This data in Fig. I prove the prevalence of cyber-violence against women in India and presents how important it is to put a curb on the same through a proper regulatory mechanism in the form of strict laws and stricter enforceability by the concerned authorities. In another response to the question on witnessing cyber-violence, an alarming percentage (39.8%) people affirmed the same, which can be observed in Fig. II.

Fig. II

The data in Fig. II presents a disturbing situation, where a significant number of people agree to the fact that they have witnessed cyber-violence, which puts forth an inference that there is a strong need for deterrence in India, which must act as a restraint in the minds of those, who think they can sit behind the computer and do anything to anyone.

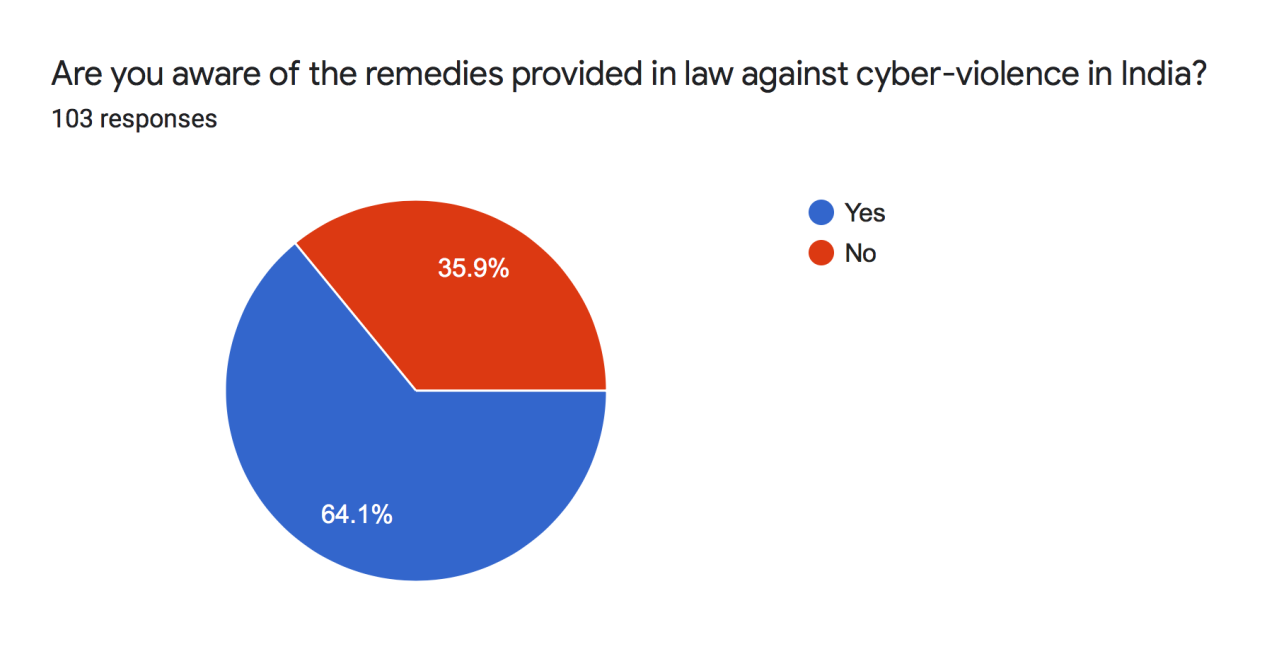

Fig. III

In another response (Fig. III), 35.9% people responded claiming that they were not aware of the remedies provided in law to address the issue of cyber-violence, which brings forth the very need of sensitization and awareness, which is lacking in India and for the same, adequate steps must be effectuated by the government to make people aware of the same as regards their rights.

There are several contentious issues, which must be addressed in full force as they prove to be an impediment in effectuating complete justice. Most common issues range from one on jurisdiction to lack of technical knowledge as regards cyberspace is concerned and the lack of proper resources in the preservation of evidence, which can easily perish.

India is currently not a signatory to any international convention or treaty, which is extremely important to mandates the states legislate, as statutory framework. The most common issues call for the revamp of complete law against cyber-violence in India.

Another criticism of the IT Act is that it lacks a proper framework on offences of cyber-violence against women. There is no mention of the word ‘woman’ or ‘girl’ in the whole IT Act except under s. 77 A, which merely mentions that the offences on the woman are not compoundable.

Lastly, the formulation of a specific international convention on cyber-violence would act as a capacity-building law for the recognition of forms of it by the states and build a responsive mechanism to address the issue.

Authored by: Tushar Arora and Aditi

National Law University and Judicial Academy, Assam

[1] Harry Newton, Newton’s Telecom Dictionary 502-3 (23rd ed., New York: Flatiron Publishing, 2007).

[2] Online gender-based violence: A submission from the APC to the United Nations Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, APC (June 26, 2020, 2:52 PM), https://www.apc.org/sites/default/files/APCSubmission_UNSR_VAW_GBV_0_0.pdf.

[3] Ann C. Seales, The Emergence of Feminist Jurisprudence: An Essay, 95(7) The Yale Law Journal 1373, 1376 (1986).

[4] Catherine A. MacKinnon, Feminism Unmodified 315 (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1987).

[5] Lata Jha, India’s Active Internet User Base to Hit 639 mn by Year-end, The Economic Times, May 08, 2020.

[6] Sumant Sen, NCRB Data: Cyber Crimes Reached a New High in 2017, The Hindu, Nov 05, 2019.

[7] Infra note 29, at 3.

[8] Dr Monika Jain, Victimization of Women Beneath Cyberspace in Indian Upbringing, Bharati Law Review, April-June 2017, at 23, 27.

[9] The Indian Penal Code, 1860, Act No. 45 of 1860 1* [6th October 1860], Acts of Parliament, 1860.

[10] The Information Technology Act, 2000, Act. No. 21 of 2000, Acts of Parliament, 2000.

[11] Saumya Uma, Outlawing Cyber Crimes against Women in India, Bharati Law Review, April- June 2017, at 35, 41.

[12] Shruti, Cybercrime Victims: A Comprehensive Study, 88(1) Harvard Law Review 144, 151 (2004).

[13] Shreya Singhal v. Union of India, (2013) 12 S.C.C. 73.

[14] Terminiello v. Chicago, 337 US 1 (1949)

[15] Supra Note 9, Sec. 4.

[16] Supra Note 10, Sec. 1(2); Sec. 75.

[17] AIR 2017 SC 150.

[18] C.C. No. 3700686/PS/2009.

[19] C.C. No. 4680/2004.

[20] (2005) 3 CompLJ 364 Del.

[21] González (‘‘Cotton Field’’) v. Mexico, Inter-Am. C.H.R. (Nov. 16, 2009).

[22] U.N. GAOR, 61st Sess., at 47, U.N. Doc. A/61/122/Add.1 (Oct. 9, 2006).

[23] Id, 17th Sess., at 7, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/17/27 (May 16, 2011).

[24] GAOR, supra note 20, 20th Sess., at 2, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/20/8 (July 16, 2012).

[25] GAOR, supra note 20, 23rd Sess., at 15, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/23/50 (Apr. 19, 2013).

[26] GAOR, supra note 20, 57th Sess., at 12, U.N. Doc. E/2013/27-E/CN.6/2013/11 (Apr 1, 2013).

[27] GAOR, supra note 20, 29th Sess., at 3, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/RES/29/14 (July 2, 2015).

[28] Combatting Online Violence against Women & Girls: A Worldwide Wake-up Call (June 29, 2020, 10:46 AM), Available Here

[29] GAOR, supra note 20, 61st Sess., at 2, U.N. Doc., A/C.3/71/L.39/Rev.1 (Nov. 16, 2016).

[30] GAOR, supra note 20, 35th Sess., at 15, U.N. Doc., A/HRC/35/9 (May 5, 2017).

[31] CEDAW/C/GC/35 (July 14, 2017).

[32] GAOR, supra note 20, 38th Sess., at 4, U.N. Doc. A/HRC/38/47 (June 14, 2018).