Hierarchy of Civil Courts in India

Learn about the structure of Civil Courts explaining the Hierarchy of Civil Courts in India.

Hierarchy Of Civil Courts In India | Overview

- Introduction

- Judicial System during the British Era

- Current Judicial System in India

- The Hierarchy and the nomenclature of these civil courts vary in different states

- Conclusion

Introduction

The judiciary, the third pillar of democracy, must suit the needs of the country if peace is to exist in the country. The structure of the courts for that purpose must be made while taking into account the conditions and circumstances of the country in question, because the structure is not fit for dispensing justice and is inefficient and acts arbitrarily, then any country can go into a situation of chaos anytime. Hence, a concrete ‘structure of courts’ and their hierarchy, and proper division of powers is important to maintain peace and dispense justice in the country.

In India, the current system of judicial system is a modified version of that model, which evolved during the British era.

Judicial System during the British Era

The British laid the foundation of a new system of dispensing justice through a hierarchy of civil and criminal courts. Though the process was initiated by Warren Hastings, the system was concretized by the structure evolved by Lord Cornwallis in 1793.

In each district, a Diwani Adalat, or civil court, presided over by the District Judge, who belonged to the civil service of the British. Cornwallis thus separated the posts of the Civil Judge and the collector, and initiated the process of separating the judiciary from the executive, and transformed the mere principle of ‘independence of judiciary’ into reality. Appeal from the orders of the district court was to go to the Provincial Councils of Appeal, and then, finally, to the Sadar Diwani Adalat.

Below, the District Court, a subordinate mechanism was created to decide the cases with less amount in dispute. The court, just below the District Court, was Registrars Courts, which used to be European Officers. A number of Indian Judges were given the offices of Munsifs and Amins, who decided cases of very small amounts and were posted remotely and locally so that justice is easily available and people are not forced to travel long distances to get the justice.

To deal with criminal cases, Cornwallis divided the presidency of Bengal into four divisions, in each of which a Court of Circuit was established, which was presided over by the civil servants of the Company.

The structure evolved by the British was new to Indians, and even the procedures evolved by the British were analogous to their system in Europe but alien to the locals, i.e., Indians; But, the law which was being applied to Indians before the British judicial system had come into existence, continued to apply, even after the British Judicial system came into existence. In civil law, Indians were governed by their customary laws which arose from the long tradition and practice.

In 1831, William Bentinck abolished the Provincial Courts of Appeal and Courts of Circuit. Their work was assigned first to Commissions and later to District Judges and Collectors. As these Commissions decided cases by holding some sessions, their court was subsequently called ‘session courts’, which remains the name even today.

Bentinck also raised the status and powers of Indians in the judicial service and appointed them as Deputy Magistrates, Subordinate Judges, and Principal Sadar Ameens. This step made the judicial system more open to the Indians and integrated them into the system, which was earlier made exclusive to the Europeans only. The reliance of the British on the Indian Judges was now increased and this gave more power to the Indians too, and representation within the judicial system.

In 1865, High Courts were established at Calcutta, Madras, and Bombay to replace the Sadar Courts of District and Nizamat. Till this point in time, the basic structure of the hierarchy of the courts was completely established, now only some minute modifications were done to adapt to the new conditions and circumstances.

Though these courts earlier applied the Indian Laws, the British introduced regulations, codified the existing laws, and often systematized and modernized them through judicial interpretation. In 1833, the Government appointed a Law Commission headed by Lord Macaulay to codify Indian Laws. Macaulay’s work eventually resulted in the Indian Penal Code, The Code of Civil and Criminal Procedure and other codes of laws. These codes are followed even nowadays, with the majority of the parts remaining unamended. This shows the superiority and fineness of the work done by the Law Commission.

This judicial architecture continued for long till the enactment of Government of India Act, 1935. It changed the structure of Indian Government from “unitary” to that of “federal.

The distribution of powers between the Centre and the provinces required a balance to avoid disputes, which would have arisen between the constituent units and the Federation.

Since the enactment categorized different legislative subjects into 3 lists, these subjects overlapped, and the number of disputes between the state and the centre with regard to infringement of each other's power became a consistent case. So, to resolve these disputes, the Act established a Federal Court, which was set up in 1937 with appellate and advisory jurisdiction. Its appellate jurisdiction was extended to civil and criminal cases.

Current Judicial System in India

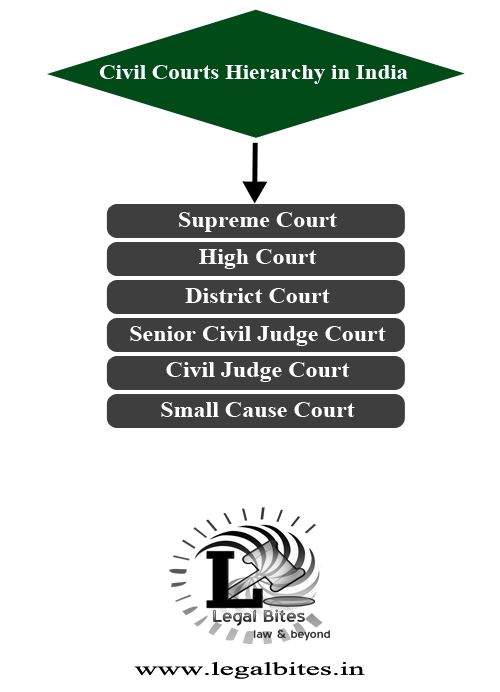

The Current Judicial System in India is broadly divided into 3 levels. The Supreme Court, i.e., the Apex court of the country covers its peak. At the middle level, come the High courts. And at its tip, lies the subordinate courts.

The Supreme Court, being the highest judicial body in the country holds the last say in any case filed in any lower court, or directly into the Supreme Court, the only exception is the power of pardon, which lies with the president in criminal cases, who can suspend the sentence awarded even by the supreme court. But, in all other matters, the power of the Supreme Court is unassailable. The Supreme Court of India was formed in Delhi and came into force on 26 January 1950. It is the highest court of land as established by Part IV, Chapter IV of the Constitution of India.

Supreme Court comprises of Chief Justice, and 33 judges (including the Chief Justice of India) and maximum possible strength is 34, currently Hon’ble Mr. Justice D.Y. Chandrachud holds the office of Chief Justice of India. The judges of the Supreme Court are appointed by the President of India, on the recommendation of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court and other senior-most judges of the Supreme court through the body of “collegium”.

Supreme Court is a court of record and has the power to punish for its contempt (under Article 129, Constitution of India). Original Jurisdiction (Art. 131) of the Supreme Court comes into play in matters of dispute between either 2 states, or between center or state, or between the center and more than 2 states, contesting the suit. Supreme Court is given powers to decide such cases in the first instance only, i.e., they can directly be filed there. Supreme Court is the Highest Court of Appeal in the country, both for civil and criminal matters (Art. 132, 133, 134 & 136).

The most important role of the Supreme Court is the protection of fundamental rights, the responsibility of it is given to the court under Article 32 of the constitution. This article confers a fundamental right on the common man of the country to directly approach the Supreme Court, where any of the fundamental rights are infringed. This right is also called the ‘heart and soul of the constitution‘.

This right cannot be suspended even during an emergency. The Supreme Court also advises the president when its advice is sought on any ‘question of law’, but it is not binding on the court to tender the advice. Ultimately, the law declared by the Supreme Court is binding on all courts in India (art. 141,). Hence, it is correctly said that the legislature ‘makes’ the law, but the Supreme Court ‘declares’ the law, and is revered as ‘guardian of the constitution in India.

Second inline comes, the High Courts. High Courts are also constitutional courts established under Part VI, Chapter V, of the Indian Constitution. High Court stands at the head of State’s Judicial administration.

There are 25 High Courts in India, six having control over more than one State/UT. Among the Union Territories, Delhi alone has a High Court of its own.

The other six Union Territories come under the jurisdiction of different State High Courts. A High Court may also have some subordinate benches other than its principal bench to accommodate the immense population of any state like Madhya Pradesh High Court has its other benches at Indore and Gwalior. The Calcutta High Court is the oldest High Court in the country, established on 2 July 1862, whereas the Allahabad High Court is the largest, having a sanctioned strength of judges at 160.

Each High Court comprises a Chief Justice and such other Judges as the President may, from time to time appoint. The Chief Justice of a High Court is appointed by the President in consultation with the Chief Justice of India and the Governor of the state.

The procedure for appointing the High Court judges is the same except that the recommendation for the appointment of Judges in the High Court is initiated by the Chief Justice of the High Court concerned. Each High Court has the power to issue any person or authority and Government within its jurisdiction, direction, orders or writs, including writs which are in the nature of habeas corpus, mandamus, prohibition, quo warranto, and certiorari, for enforcement of Fundamental Rights and for any other purpose, hence, the High courts are also called Writ Courts.

High Courts are also courts of Record and have the power to punish for contempt. With regard to original jurisdiction, the powers of the High Court are very narrow and limited, only some cases like Election Petitions directly come into the High Court, otherwise, primarily High Court is an appellate court. High Courts also have revisional jurisdiction conferred under the Civil and Criminal Procedure Code.

Administratively, Each High Court has powers of superintendence over all courts within its jurisdiction. It can call for returns, from such courts, to make and issue general rules and prescribed formats to regulate their practices and proceedings and determine the manner and form in which book entries and accounts shall be kept.

Last in line, comes the Subordinate Courts. Chapter VI of Part VI of the Indian Constitution has made provisions for subordinate courts related to the judicial system. The structure and Functions of Subordinate Courts are more or less uniform throughout the country.

The structure and functions of subordinate courts are more or less uniform throughout the country. Designations of courts connote their functions. These courts deal with all disputes of a civil or criminal nature as per the powers conferred on them. These courts have been derived principally from two important codes prescribing procedures, i.e., the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 and the Code of Criminal Procedure, 1973 and further strengthened by local statutes.

As per the direction of Supreme Court in WP (Civil) 1022/1989 in the All India Judges Association case, a uniform designation has been brought about in the subordinate judiciary’s judicial officers all over the country viz., District or Additional District Judge, Civil Judge (Senior Division) and Civil Judge (Junior Division) on the civil side and on the criminal side, Sessions Judge, Additional Sessions Judge, Chief Judicial Magistrate and Judicial Magistrate, etc., as laid down in the Cr.P.C.

Appropriate adjustment, if any, has been made in existing posts by indicating their equivalent with any of these categories by all State Governments/UT Administrations.

Under Article 235 of the Constitution of India, the administrative control over the members of subordinate judicial service vests with the concerned High Court.

Further, in the exercise of powers conferred under the provision to Article 309 read with Articles 233 and 234 of the Constitution, the State Government shall frame rules and regulations in consultation with the High Court exercising jurisdiction in relation to such State. The members of the State Judicial Services are governed by these rules and regulations.

The jurisdiction of a civil court is assigned by assigning a particular territory or town under that court, and also assigning a particular pecuniary limit, i.e, monetary jurisdiction. The value of pecuniary jurisdiction assigned to a particular court varies from state to state.

The Hierarchy and the nomenclature of these civil courts vary in different states.

In Delhi, for instance, there are very broadly following levels of civil courts.

- District Judge & his collateral additional District Judges

- Senior Civil Judge

- Civil Judge

- Small Cause Courts.

Civil cases up to the monetary value of three Lakhs are filed before the Civil Judges. Civil cases having a monetary value between three Lakhs and twenty Lakhs are filed before the District Judge or Additional District Judge. Civil cases having a monetary value above twenty Lakhs are filed directly in the High Court.

The Small Cause Courts are established to adjudicate upon small cause matters such as guardianship and custody matters which can be adjudicated in a summary trial that is, without a protracted and extensive civil trial.

The court of Civil Judge, Senior Civil Judge, and Additional District Judges, on the other hand, entertain regular matters requiring proper civil trial following all the rules of evidence and procedures envisaged in the civil procedure code.

Besides these subordinate courts, to dispense speedy justice, there are some special courts, made for specific purposes, created under specific statutes, to resolve cases on specific matters.

Such as courts made under the State Lokayukta Acts, Special Courts under the Essential Commodities and Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances Act (EC & NDPS Act), also special tribunals dealing with the disputes of tax, Labour, and Copyright cases. All this increases the pace of dispensing justice in certain matters.

Also, at remote levels, panchayat courts are constituted, and they compose a system of alternative dispute resolution. They were recognized through the Madras Village Court Act of 1935, in various provinces. The model of the Gujarat state, with a judge and two assessors, was used from the 1970s onwards. In 1984 the Law Commission recommended creating Nyaya Panchayats in rural areas with laymen (“having educational attainments”).

The 2008 Gram Nyayalayas Act have foreseen 5,000 mobile courts in the country for judging petty civil (property cases) and criminal (up to 2 years of prison) cases. However, the Act has not been enforced properly, with only 151 functional Gram Nyayalayas in the country (as of May 2012) against a target of 5000 such courts. The major reasons behind the non-enforcement include financial constraints, and the reluctance of lawyers, police and other government officials.

A new alternative dispute resolution mechanism is created in the form of ‘Lok Adalat’, where the disputes/ cases pending in the court of law or at the pre-litigation stage are settled/compromised amicably.

The Adalat has been given statutory status under the Legal Services Authorities Act, of 1987. Under, this Act, an award made by a Lok Adalat is deemed to be a decree of a civil court and is final and binding on all parties and no appeal lies against thereto before any court.

The act stipulates the establishment of a Permanent Lok Adalat for exercising jurisdiction in respect of disputes relating to Public Utility Services, such as transport service, postal, communication, the supply of power, service in hospitals/dispensaries, insurance services and such Lok Adalats for Public Utility Services have been established in 16 states/UTs.

Conclusion

Though the current mechanism of justice dispensation in India has many advantages, the primary one being its adaptation by the citizens of the country and its becoming an integral part of the country, even then its inefficiency is undoubted. Numerous changes are needed to make it more efficient and speedy in its process.

The number of judges needs to be increased, with the number of courts too. Many more remote courts also are needed to be established, so that justice does not remain exclusive to urban and affluent people.