Homecoming - The Citizenship (Amendment) Bill, 2019

Introduction The Lok Sabha, on 8 January 2019, passed the contentious Citizenship (Amendment), Bill. The legislation seeks to facilitate the granting of citizenship to the identified minorities, namely Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Christians, and Parsis, escaping religion-based persecution from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh and entering India before December 31, 2014. The mandatory period of residence has been reduced… Read More »

Introduction

The Lok Sabha, on 8 January 2019, passed the contentious Citizenship (Amendment), Bill. The legislation seeks to facilitate the granting of citizenship to the identified minorities, namely Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Christians, and Parsis, escaping religion-based persecution from Pakistan, Afghanistan, and Bangladesh and entering India before December 31, 2014. The mandatory period of residence has been reduced to seven years instead of 12 years (as was the norm currently), with exceptions created for possession of required documents for the same.

While introducing the Bill, Union Home Minister Rajnath Singh clarified that its applicability would not be limited to just Assam and the Northeast. Beneficiaries would be free to reside in any part of the country, and that it merely seeks to initiate the process for acquisition of citizenship; it would be granted only after due scrutiny and recommendation of district authorities and State Governments.[1]

The Citizenship Amendment Bill and the Assam Accord

In highlighting the ‘divisive’ and ‘flawed’ nature of the Bill, the opposition has mostly relied on provisions of the Assam Accord. The 1985 Accord was signed between the Rajiv Gandhi government and the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU), six years after the anti-illegal immigrant Assam Movement. As a result, section 6A was inserted in the Citizenship Act, 1955, which resulted in non-citizens entering Assam between before 1971 enjoying all citizen rights (with the exception of voting rights for 10 years for those entering between 1966 and 1971), along with the promised deportation of migrants entering post-March 1971.

Under the Accord, the State began to draw a causal link between economic development and those deemed as illegal aliens, as seen by its safeguards aiming at protecting the heritage of the Assamese people, and ‘the all-round economic development of Assam’.[2] The Home Affairs Ministry sought to initiate the implementation of these provisions, by announcing a High-Level Committee with a very wide mandate to suggest these safeguards, with possible reservation in the State Assembly and government jobs.[3]

The opposition argues that the Bill seeks to legitimize the stay of all illegal immigrants in the first place, something that the Accord clearly opposed. And while the government is doing so, there seems to be a deliberate ploy to create an exception for the Muslims, who have been left out as per current provisions of the Bill. The government, it has been argued, has left out members of certain Islamist minority communities who too face majoritarian religion-based persecution in the neighboring countries.

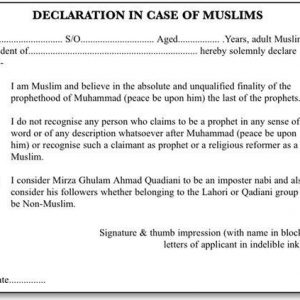

An example cited to affirm the same is the persecution faced by the Ahmadiyya Muslims in Pakistan. The Second Amendment to its Constitution declares them to be non-Muslims, with enactments such as Ordinance XX thereby depriving them of their right to freely practice the distinct tenets of their religion within the broad Islamist sect.

The declaration required to be made while applying for a Pakistani passport. It refuses to acknowledge Ahmadis as Muslims.

In contrast, the Ahmadis are considered to be Muslims by law in India. While they are not allowed to participate in the affairs of bodies such as the All India Muslim Personal Law Board, the Constitution guarantees to them the Fundamental Right to freely practice, profess, and propagate their religion.[4] The Kerala High Court, in Shihabuddin Imbichi Koya Thangal vs K.P. Ahammed Koya, determined that Ahmadis are Muslims owing to their allegiance to the two core beliefs of Islam: that there is no god but Allah and that Muhammad is a messenger of God.[5]

Hence, it has been argued that the bill is violative of article 14 of the Constitution because it treats equals unequally. What can be said to be equal in this scenario is the fact that all of these communities face religious persecution of one form or the other. Be it as exclusionist as it is in the case of the Ahmadiyya Muslims, or the separation faced by the Hindus in Pakistan. But, unequal treatment is being meted out to them because one set of communities are getting a favorable shot at Indian citizenship, while the others are being deliberately left out (due to a wider perception of a community’s integration within the larger sects of Islam).

Assam and its History of Migration

Historically free from large external influence, Assam has been a large multi-ethnic society with divisions on the basis of ethnicity, language and culture, and with a profound history of immigration. This was first seen during the colonial period from other parts of the subcontinent as indentured labor in the tea gardens. The Partition in 1947 led to the creation of two nation-states on the basis of religion, thereby prompting further to-and-fro migration. Finally, the war in 1971, which left one of those nation-states further broken up owing to political exclusion and ethnolinguistic discrimination, led to the largest influx ever witnessed.

The broad influx of Bengalis from the newly-created Bangladesh aggravated an already worsening ‘anti-foreigner’ feeling in Assam. These feelings emerged primarily owing to the Assamese pride in their ethnicity and language, and a general feeling of socio-economic subordination to the Bengalis. The feelings soon turned into an obvious fear of being reduced to a minority in their own land, which had been further piqued with suspicion over the legal status of the ‘foreigners’.[6]

Those who oppose the migration claim that, if the illegal migrants would be allowed in the state, they (migrants) would take away the resources belonging rightfully to the natives of the state. It is also feared that the illegal migrants would irrevocably dilute the strength of the indigenous Assamese population.

Initiatives to tackle the problem of illegal immigration in Assam have always suffered the problems of poor conceptualization, inefficiency, and corruption. The 1950 Immigrants (Expulsion from Assam) Act granted the central government power to remove those immigrants whose stay was detrimental to the economic interests of India. The Act had to be repealed because of an inherent bias against Muslims in favor of Hindus.

The Prevention of Infiltration to Assam Plan, adopted in 1964, fetched immediate results: the identification, arrests, and deportation of 190,000 illegal immigrants during the first three years of implementation. In the subsequent years, its execution failed miserably, with the detention and subsequent return of just one person in 1976.[7]In that context, the reason why the Assam Movement was very popular in being able to mobilize popular support was that it was able to frame the question of immigration in terms of the Constitution and laws of India. The Movement was able to present a clear contradiction: by suggesting that the Constitution showed a clear degree of acceptance towards certain migrants, as well as the non-acceptance of other immigrants. That the only immigrants whose stay in Assam was considered lawful were those whose descendants had stayed for a long enough duration in the State.[8]

Hence, now that the Bill seeks to set a new cut-off date for Bengali Hindus, tensions prevail not just across Assam, but the whole of Northeast India. The estimated 9 lakh Bengali Hindus who entered Assam between 1971 and 2014 could possibly go on to become Indian citizens. In Mizoram, too, about 10,000 Chakmas (of Buddhist origin) who have fled oppression in Bangladesh would present a strong case for Indian citizenship.[9]

It has been feared that several of these states could end up how Tripura did, where unabated illegal immigration resulted in the indigenous tribal communities being reduced to a minority in their own land.

Repercussions on the National and Subcontinental Levels

It has also been argued that the proposed amendment could well embolden the political forces that evict such minorities from their lands and force these communities to enter India.[10] Given the history of the subcontinent, minorities have always been suspected of dual loyalty, especially in times of communal strife.[11] When the Indian State goes on to open its arms for granting citizenship to the oppressed communities, the results would be the opposite of what was intended. Hence, the Bill would immediately benefit only those members of the communities, who have successfully moved to India and now live as members of the majority community, after being issued Long-Term Visas on the basis of their claims of religious persecution.[12]

When the bill is taken in light of the update of the National Register of Citizens (NRC) in Assam, a sense of unilateralism prevails. This can be attributed to the fact that the government of India has barely engaged on this matter with the Bangladesh government (whose official position remains that there are no unauthorized Bangladeshi immigrants in Assam).[13] Any such engagement seems extremely unlikely, given the ‘neighbourhood first’ policy adopted by the present Indian regime.[14]

In stark contrast, governments in the past have shown the will to participate in a bilateral dialogue on the issue of immigration (the Nehru-Liaquat pact being a prime example), especially when it comes to reassuring safety to the minorities and discouraging migration to whatever extent possible.[15]

The Bill, thence, could ensure that non-Muslims excluded left out of the final NRC list are eventually included, given that out of the excluded 40 lakh people, 22 lakh were Hindus.[16] The threat of the exercise being rendered futile seems larger than ever before. While the right of appeal would certainly be granted, it can very well be said that other communities could well lose out on what Hannah Arendt called ‘the right to have rights’, especially with the state’s focus being on detention (with large-scale deportation almost ruled out).[17]

Having accepted this, it becomes clear that this Bill, coupled with the attitudes of governments across borders, has every potential to possibly redraw the demographic map of South Asia, thus giving a fillip to the now discredited two-nation theory of the Partition of 1947. Critics question the exclusion of Muslim minorities from Nepal and Sri Lanka, along with several other communities such as the Ahmadis, Rohingyas from Myanmar, Tamils from Sri Lanka, and Uighur Muslims from China.

The Bill’s sole focus on religion-based discrimination seems to be just the tip of the iceberg, and it is wondered why the legislation avoids venturing into other forms of persecution, on the basis of language and ethnicity. If India is to be a regional altruist towards minorities and the idea is to play the role of a Big Brother, then this altruism should ideally have been unfettered.

It cannot be said that the concerns of the communities that are being offered protection are illegitimate or do not merit action. However, the exclusion of several communities is what is leading to a backlash over the Bill on the subcontinental sphere, while the Northeast seems to be concerned more with the retention of a distinct sense of identity and much-emphasized cultural assertions.

The series of bandhs across the Northeast, the pulling out of the Asom Gana Parishad from the ruling alliance in Assam, and the resolutions adopted by the State Assemblies give reasons for the government to perhaps have a rethink at the repercussions of this legislation and consider the views of all stakeholders. Only then can a permanent solution can be arrived at, by striking a balance between the inalienable human rights of the minorities across South Asia, the national interests of India, and the consequences this would have in the Northeast and beyond.

By – Shikhar Aggarwal

National Law University Delhi

Sources

[1] Press Release, ‘Union Home Minister introduces the Citizenship Amendment Bill, 2019 in Lok Sabha’ (Press Information Bureau, 8 January 2019) <http://pib.nic.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=187310> accessed 11 January 2019

[2] Archit Guha, ‘The Illegal Immigrant Identity and Its Fragments – From Enemy Foreigner to Bangladeshi Illegal Immigrant in (Post) Colonial India’ 12 Socio-Legal Rev. 108 (2016)

[3] Press Release (n 1)

[4] Article 25, Constitution of India

[5] Shihabuddin Imbichi Koya Thangal vs K.P. Ahammed Koya AIR 1971 Ker. 206

[6] Sanjib Baruah, India Against Itself: Assam and the Politics of Nationality (first published 1999, OUP 2010)

[7] Amiya Kumar Das, Assam’s Agony: A Socio-Economic and Political Analysis (1982)

[8] Baruah (n 5)

[9] Jaideep Mazumdar, ‘Citizenship Bill can prove Electorally costly for the BJP in the North East’ (Swarajya, 9 January 2019) accessed 11 January 2019

[10] Sanjib Baruah, ‘Citizens, non-citizens, minorities’ (Indian Express, 28 June 2018) accessed 11 January 2019

[11] ibid

[12] ibid

[13] ibid

[14] Sanjib Baruah, ‘Stateless in Assam’ (Indian Express, 19 January 2018) accessed 11 January 2019

[15] Baruah (n 9)

[16] Parvin Sultana, ‘Modi’s Citizenship Amendment Bill could have the Northeast in Flames’ (Huffington Post, 11 January 2019) <https://www.huffingtonpost.in/entry/assam-citizenship-amendment-bill-bjp-nrc-narendra-modi_in_5c376743e4b045f67689a935> accessed 11 January 2019

[17] Baruah (n 13)

Disclaimer: Legal Bites is determined to include views and opinions from all sides of the spectrum. This doesn’t mean we agree with everything we publish. But we do support their right to the freedom of speech. In case of content writers/editors/bloggers articles, the information, ideas or opinions in the articles are of the author and do not reflect the views of Legal Bites. Legal Bites does not assume any responsibility or liability for the same.

- Click Here for more Articles.

- Click Here to write your own Blog/Article on Legal Bites.