Intellectual Property: Protection of Artificial Intelligence – A Debatable Matter - by Vaishnavi Sabhapathi

Introduction Intellectual property is a legal lexicon which refers to creations of the mind for which exclusive rights are recognized. Under Intellectual Property law, owners are guaranteed certain exclusive rights to a variety of intangible assets, such as musical, literary, and artistic works; discoveries and inventions; and words phrases, symbols, and designs. Common ways of protecting intellectual property… Read More »

Introduction

Intellectual property is a legal lexicon which refers to creations of the mind for which exclusive rights are recognized. Under Intellectual Property law, owners are guaranteed certain exclusive rights to a variety of intangible assets, such as musical, literary, and artistic works; discoveries and inventions; and words phrases, symbols, and designs.

Common ways of protecting intellectual property rights include copyright, trademark, patents, industrial design rights, trade dress, and in some jurisdictions trade secrets. Intellectual property rights are the rights given to persons over the creation of their minds. They usually give the creator an exclusive right to the use of his/her creation for a certain period of time.

Although many of the legal principles governing intellectual property rights have evolved over centuries, it was not until the 19th century that the term intellectual property began to be used, and not until 20th century that it became commonplace in the majority of the world.[1].

In light of recent extraordinary progress, we may be on the point of a revolution in robotics and artificial intelligence (AI) technology wherein machines will be able to do anything people can, and more.[2] Recent successes have demonstrated that computers can independently learn how to perform tasks, prove mathematical theorems, and engage in artistic endeavors such as writing original poetry and music and painting original works.[3]

Artificial intelligence (AI) is pushing innovation in new ways and accelerating with technological advancements in computing power, data, and algorithms. As technology advances so too do the ability to use AI tools in previously unachievable ways. This has led to a recent uptrend in AI deployment by companies ranging from start-ups to long-established institutions. Intellectual property (IP) protects and encourages innovation and creativity.

LEGAL PERSONALITY OF ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Legal personality is an artificial creation of law. Entities recognized by law are capable of being parties to a legal relationship. A natural person is a human being whereas legal persons are artificial persons such as a corporation, created by law and given certain legal rights and duties of a human being” a being, real or imaginary, who for the purpose of legal reasoning is treated more or less as a human being.[4]

Legal personhood is invariably linked to individual autonomy but has however not been granted exclusively to human beings. The law has extended this status to non-human entities as well, whether they are corporations, ships, and other artificial legal persons.[5] No law currently in force in India recognizes artificially intelligent entities to be legal persons, which has prompted the question of whether the need for such recognition has now arisen. The question of whether legal personhood can be conferred on an artificially intelligent entity boils down to whether the entity can and should be made the subject of legal rights and duties.

The essence of legal personhood lies in whether such entity has the right to own property and the capacity to be sue and be sued.[6]

On the other hand, AI cannot be treated on par with natural persons as AI lacks:

- Soul,

- Intentionality,

- Consciousness,

- Feelings,

- Interests, and

- Free will.[7]

CURRENT LEGAL FRAME IN INDIA REGARDING ARTIFICIAL INTELLIGENCE

Status of AI under Indian Law

The Constitution of India is the basic legal framework which allocates rights and obligations to persons or citizens. Unfortunately, Courts are yet to adjudicate upon the legal status of AI machines, the determination of which would clear up the existing debate of the applicability of existing laws to AI machines.

Protection of Intellectual Property

When the remarkable extent of creativity and knowledge exhibited by AI is clearly visible, concerns pertaining to IP protection ought to be there in the minds of those enforcing the rights associated with the intellectual property.

There is a wide variety of intellectual property legislation which would impact/affect the functioning of AI in India. Such legislation is discussed in detail below.

a) Copyright

In some countries, we can see a conspicuous requirement of creativity, when it comes to the ownership of copyright works. Even Indian Copyright law requires that in order for a ‘work’ to qualify for copyright protection, it would first have to meet the ‘modicum of creativity’ standard laid down in “Eastern Book Company and Ors. v. D.B. Modak and Anr”.[8]

In the above case, the Court held that a ‘minimal degree of creativity’ was required, that there must be ‘there must be some substantive variation and not merely a trivial variation’. From a reading of the test laid down in the aforementioned judgment, however, there is no definitive conclusion that may be arrived at wherein it may be stated that an AI cannot meet the ‘modicum of creativity’ as required.

In addition to the above, the second requirement to be satisfied by an AI when it comes to the ownership of copyrighted works is the requirement to fall under the aegis of an ‘author’ as is defined under the Copyright Act, 1957. This would be problematic as an AI has generally been regarded to not have a legal personality.

Under Section 2 (d) of the Copyright Act, 1957,

“(d) “author’ means,-

“(vi) In relation to any literary, dramatic, musical or artistic work which is computer-generated, the person who causes the work to be created;”

The first problem under the above-mentioned definition is its usage of the terms ‘the person who causes the work to be created’. Determining who ‘causes’ a work to be created is a question of the proximity of a natural or legal person to the creation of the ‘expression’ in the content in question – the more closely or directly a person is involved in creating the ‘expression’, the more he or she contributes to it, and the more likely he or she is to qualify as a person ‘who causes the work to be created’. As a result of the above, the current legal framework under the Copyright Act, 1957 may not effectively deal with/prescribe for the creation of works where the actual creator or a contributor of the ‘expression’ is not a human or a legal person.

Thus, when it comes to works that are created by AI, their authorship would be contentious under Indian copyright laws. There is no doubt that a human’s involvement is required in kick-starting the AI’s creative undertaking, however, the process to determine who the author owner is when the AI steps in to play a pivotal role in the creation of the work continues to remain a grey area.

b) Patents

Section 6 of the Indian Patents Act, 1970 states that an application for a patent for an invention can be made only by the true and first inventor of the invention or the persons assigned by such person.[9]

Whereas, Section 2 (y) of the Act confines the definition of “true and first inventor” to the extent of excluding the first importer of an invention into India, or a person to whom an invention is first communicated outside India, and nothing further.[10]

These provisions do not expressly impose the requirement of an inventor to be a natural person. Therefore, from a bare reading of these provisions, it may be interpreted that an AI may fall under the definition of an inventor as provided in Section 2(y) of the Indian Patents

Act, 1970. However, in practice, the “true and first inventor” is always assumed to be a natural person. Thus, it will be interesting to track the jurisprudence on this front especially the stand taken by the patent office when the “true and first inventor” on the patent application form is not a natural person.

However, AI will certainly play an important role in the evolution of patent law itself.

Sophisticated use of natural language processing has been adopted in generating variants of existing patent claims so as to enlarge the invention’s scope. The publication of these patent claims using such technology would help preclude obvious and easily derived ideas from being patented as they will form the corpus of the prior art that is available in public domain.[11]

If the trend of using such services gains a foothold in the industry, it will substantially increase the uncertainty associated with the enforceability of a patent as the risk of not discovering prior art that invalidates the patent would increase.[12] As a result, it could be anticipated that AI would be developed to assist in the discovery of prior art and correspondingly this would certainly increase the demand of AI (from a patent law perspective) in this sector.

c) Industrial Designs

With the progress of artificial intelligence advancements like Watson, Siri, and Alexa, it can be observed that many companies are working on different forms of smart intelligent machines at present that could aid in its overall and inclusive development. In the process of creation of Industrial Designs where numerous components come together at an effective level to emerge to the final stage, Computer-aided Design and Drafting (CAD) systems have their own limitations confining itself to only geometric models and representations.

On the other side, the recent headway in generative techniques where an AI is associated in the process could be a more creative and systematic way of providing mechanical solutions, thereby undergirding the industrial design process.

Section 1(j) (iii) of the Designs Act, 2000 interestingly defines the “Proprietor of a new or original design” as the author of the design and any other person too, where the design has de-evolved from the original proprietor upon that person. So, how do we successfully determine the rightful authorship if an artificial entity such as an AI is behind the original design? Also, what are the odds of an AI acknowledging the authorship of a design?

In addition to that, what is the possibility of authorship of the design being devolved from the AI to a human being, when the AI itself does not have the elementary cognizance as to what a proprietorship/authorship would mean in its strict legal sense? These questions remain unanswered but it is anticipated that jurisprudence on the same shall soon evolve.

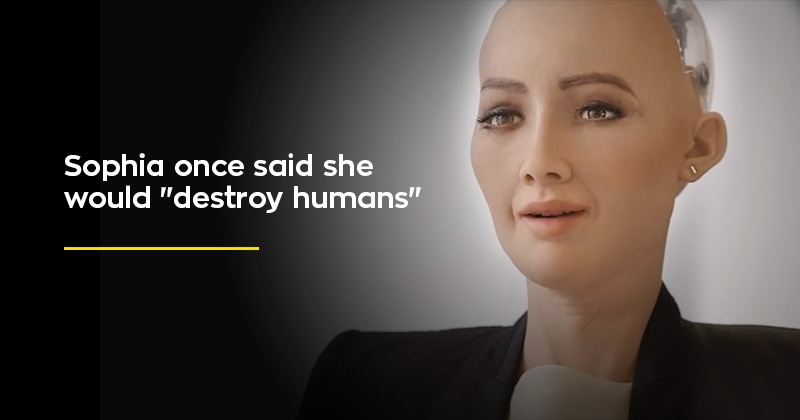

CASE STUDY OF SOPHIA CASE – REVOLUTION IN ROBOTS

Sophia, an advanced humanoid robot created by Hong Kong-based Hanson Robotics, uses artificial intelligence, facial recognition, and strikingly human-like expressions.

On October 25, Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to Sophia, making “her”[13] the first robot to achieve that distinction in the world. Though many have speculated as to the motives of this ostentatious move on the part of the Kingdom, conveniently in the midst of the Future Investment Initiative in Riyadh,[14] this development does more than raise doubts as to the King’s sincerity—rather, it highlights yet again the cavernous gap between today’s technology and the legal regulation regimes developed thus far.

CONCLUSION

Artificial Intelligence is not anymore emerging idea but it is already here now. This paper has addressed how the old concepts of Intellectual Property are being stretched to the maximum to accommodate the disruptive consequences of the advent of Artificial Intelligence.

Adequate and definite legal protection would be necessary to properly incentivize Artificial Intelligence inventors and investors, as well as to unlock the economic potential related to this new technology while ensuring a fair balancing of the interests of all stakeholders involved.

However, no significant result has been achieved, Europe and the U.S. have been addressing AI-related issues with discontinuity and a call for legislative action may be advisable. Courts efforts to re-interpret patent law to duly protect Artificial Intelligence may end up in putting into question the very foundation of patent law itself, it is exemplificative that, for instance, the very prerequisite of patentable subject matter has been diluted in the context of the U.S. case law to extend the umbrella of protection granted under patent law.

On the other hand, the attempt to reward the owners of artificial intelligence systems, by allowing a return for the inventions or works of art created by AI, poses serious threats to the notion of inventorship and authorship, thus undermining the fundamental principles of both patent and copyright law.

The problems doesn’t end just by creating the protection of the Artificial Intelligence but would further pay the way for more legal complexes as to such AI’s civil and criminal liabilities.

– Vaishnavi Sabhapathi

Content Writer at Legal Bites

References:

[1] Mark.A.Lemley, Property, Intellectual Property, and Free Riding, Texas Law Review, 2005, Vol.83:1031

[2] “Rise of the Machines” (2015) The Economist available at http://www.economist.com/news/briefing/21650526-artificial-intelligence-scares-peopleexcessively-so-rise-machines

[3] R King, “Rise of the Robo Scientists” (2011) 304 Scientific American 72-77, at 73; P Marks, “Eureka Machines” (2015) 227 New Scientist 32-35; R Plotkin, The Genie in the Machine: How Computer-Automated Inventing is Revolutionizing Law & Business (Stanford: SUP, 2009), at 67; E Knorr, “Origin of the Patents” (2001) MIT Technology Review available at https://www.technologyreview.com/s/401134/origin-of-the-patents/

[4] Black’s Law Dictionary, 8th Edition.

[5] Migle Laukyte, ‘Artificial and Autonomous: A Person?’ (2012) Social Computing, Social Cognition, Social Networks and Multiagent Systems Social Turn.

[6] L. B. Solum. Legal Personhood for Artificial Intelligences. North Carolina Law Review, 70: 1231–1287 (1992).

[7] L. B. Solum. Legal Personhood for Artificial Intelligences. North Carolina Law Review, 70: 1231–1287 (1992).

[8] Appeal (civil) 6472 of 2004

[9] Section 6 of the Indian Patents Act, 1970.

[10] Section 2(y) of the Indian Patents Act, 1970

[11] Erica Fraser, “Computers as Inventors – Legal and Policy Implications of Artificial Intelligence on Patent Law”, (2016) 13:3 SCRIPTed 305 https://script-ed.org/?p=3195.

[12] Erica Fraser, “Computers as Inventors – Legal and Policy Implications of Artificial Intelligence on Patent Law”, (2016) 13:3 SCRIPTed 305 https://script-ed.org/?p=3195.

[13] The issues associated with identifying a robot with gendered personal pronouns were specifically brought to light in Chris Weller, We Couldn’t Figure out Whether to Call the First Robot Citizen ‘She’ or ‘It’ — And It Reveals a Troubling Truth About Our Future, BUS. INSIDER (Oct. 26, 2017 2:10 PM), http://www.businessinsider.com/sophia-the-robot-blurs-line-between-human-and-machine-2017-10. This article will refer to Sophia by name whenever possible to avoid the issue.

14] See James Vincent, Pretending to Give a Robot Citizenship Helps No One, VERGE (Oct. 30, 2017, 1:00 PM), https://www.theverge.com/2017/10/30/16552006/robot-rights-citizenship-saudi-arabia-sophia; Weaver.