Wakf under Muslim Law : Concept, Creation, Control and Registration

Introduction A wakf under Muslim law is essentially a religious and pious obligation, though provision is sometimes also made for charities and for the benefit of oneself, one’s children and descendants (alal-aulad). The origin of wakf is traced to an utterance of the Prophet. The utterance is often quoted and is considered the briefest definition of Wakf –… Read More »

Introduction A wakf under Muslim law is essentially a religious and pious obligation, though provision is sometimes also made for charities and for the benefit of oneself, one’s children and descendants (alal-aulad). The origin of wakf is traced to an utterance of the Prophet. The utterance is often quoted and is considered the briefest definition of Wakf – “Tie up the substance and give away the fruit”. However, in the early days of Islam, the law of wakfs suffered from...

Introduction

A wakf under Muslim law is essentially a religious and pious obligation, though provision is sometimes also made for charities and for the benefit of oneself, one’s children and descendants (alal-aulad). The origin of wakf is traced to an utterance of the Prophet. The utterance is often quoted and is considered the briefest definition of Wakf – “Tie up the substance and give away the fruit”. However, in the early days of Islam, the law of wakfs suffered from great uncertainty. It was only in the second century after the flight that a body of rules based on ijma (consensus) were developed which might be considered to be the basis of the law of wakfs.

In the centuries that followed not merely the land but all types of property, movable and immovable were made the subject matter of wakfs. In the course of time, the Muslims world found that the “dead hand” (as wakfs were figuratively called and which in fact they had become) was trying to strangulate all progress and prosperity. Vast stretches of land and all other types of properties were dedicated to wakfs all over the Muslims world. In India, there are about one lakh wakfs valued at more than a hundred crores of rupees.

Instances of the mismanagement of the wakfs are numerous; the incompetence and corruption of the mutawallis are appalling and abysmal; more often than not, the properties of the wakfs are squandered away.

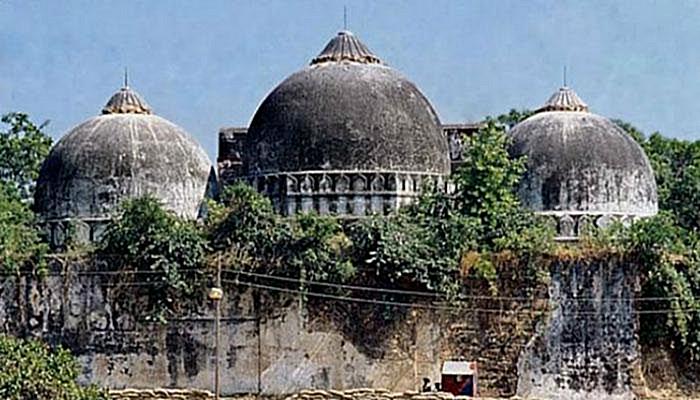

Under Muslim law, there are several religious institutions for which a wakf can be created. Important among them are a mosque, graveyard, dargah, takia, khanqah, and imambara.

Definition of wakf

The word wakf literally means ‘detention’. Abu Hanifa defined wakf as

“the tying up of the substance of a property in the ownership of the wakif and the devotion of the usufruct, amounting to an aryia, or commodate loan for some charitable purpose.”

This means that, according to him, the ownership in wakf property continued to be vested in the owner, and its usufruct was spent for charitable or pious purposes. Also, he believed that the tying up of the property was not of a permanent nature. His two disciples, however, took a different view.

According to Abu Yusuf and Imam Mohammed, wakf is the “tying up of the substance of a thing under the rule of the property of Almighty God for any purpose by which its profit may be applied for the benefit of His creatures.” However, Muhammed thought that the right of the wakif was not extinguished until he appointed a muttawali, while Abu Yusuf took the view that the right of the wakif was extinguished the moment he made the declaration.

Abu Yusuf’s definition came to be established in view of the wakf and of the Hanafi School. The definition of wakf has three essential elements:

- The ownership of the wakif is extinguished;

- The property is vested in the ownership of God perpetually and irrevocably; and

- The usufruct of the property is used for the benefit of mankind.

The Shia law defines a wakf in a different manner. According to Sharia-ul-Islam, a wakf is a contract, the fruit or effect of which is to tie up the original of a thing and to leave its usufruct free.

The Wakf Act, 1913, Section 2, defines wakf. Accordingly, it means the permanent dedication by a person professing the Mussalman faith of any property for any purpose recognized by the Mussalman law as religious, pious or charitable. Thus the purpose must be religious, pious, or charitable, the dedication of property must be permanent, and the usufruct must be utilized for the good of mankind. [Kani Ammal v. Tamil Nadu Wakf Board [1983 AP 188]

Doctrine of Cypres

Cypres literally means “as near as possible”, the doctrine lays down that if a charitable intention has been expressed by the dedicator, a wakf (or trust) will not be allowed to fail because the object specified by the settlor has failed; in such a case the income will be applied for the benefit of the poor or to objects as near as possible.

Essentials/Characteristics of a Wakf

- Property vests in god – Once the dedication of the property is made to the wakf, the ownership of the wakf is transferred to god. [Md. Ismalia v. Thakur Sabif Ali, 1962 SC 1722] Under the Shia law also the property of wakf vests in god. Thus it seems to be that in respect of wakf property in god there is no distinction between a Shia wakf and Sunni wakf or a public wakf or private wakf.

- Wakf must be Permanent – A Muslim wakf must be created for an unlimited period. In short, perpetuity is an essential feature of a wakf. Even in the case of a family wakf, the ultimate benefit must be expressly or impliedly reserved for the poor or for any other purpose of a permanent character. [Rahlman v. Bagridan, 1936 Oudh 213]

- Wakf must be Irrevocable – The irrevocability is another characteristic feature of a wakf. Once constituted validly, a wakf cannot be revoked. If in a wakfnama a conditions is stipulated that the wakif reserves to him the right of revoking the wakf or the wakf will stand revoked on the happening of any event, then such a wakf is void. [Asoobai v. Noorbai, (1906) 8 Bom LR 18]

- Wakf properties are Inalienable – Once a property is dedicated to the god, they can’t be alienated. However this rule is not absolute and in some circumstances, it is permissible that a mutawalli may alienate the wakf properties, a mutawalli may sell or grant a lease of the wakf properties with the prior permission of the court. When a wakfnama allows selling wakf properties in some circumstances, then the mutawalli has the power to alienate wakf properties in those circumstances.

Who can make a wakf: Capacity to make a wakf

Any Muslim who has attained the age of majority i.e. 18 years, and who is of sound mind, may make a wakf. A wakf cannot be made by a guardian on behalf of the minor, such a wakf is void. [Commissioner of Wakf v. Md. Mohsin, (1953) 58 Cal WN 252]

The Mussalman Wakf Validating Act, 1913, and the Wakf Act, 1954, contemplate that a wakf can be made only by a Muslim. Similarly, the Wakf Act, 1954, defines a wakf as meaning a permanent dedication by a person professing Islam. But the Nagpur High Court has expressed the view that a non-muslim can also make a wakf – the law only requires that “the object should be lawful and in consonance with Islam”. [Moti Shah v. Abdul Gaffar, 1953 Nag 38]

Subject-matter of Wakf

In the beginning, the subject matter of wakf consisted of properties of a permanent nature, such as land, fields, gardens, etc. But gradually all sorts of properties were made the subject matter of the wakfs. It is necessary that at the time when a wakf of a property is made it must be under the ownership of the person making it. [Commissioner of Wakf v. Md. Mohsin, (1953) 58 Cal WN 252] A property subject matter to mortgage or lease can also be given for the creation of valid wakf.

A wakf that forms part of a transaction to fraud on the heirs is void and totally ineffective. [Har Prasad vs. Fayaz Ahmed, 1933 PC 83]

How is wakf created?

Muslim law does not recognize any form of creating a wakf. A wakf may be made in writing or may be oral. There must be appropriate words to show an intention to dedicate the property. The use of the word wakf is neither necessary nor conclusive. To constitute a wakf it is not necessary that the word ‘wakf’ should be used. A grant to the Kazi is compulsory for the purposes of his performing religious or pious duties to constitute a wakf.

- By an act inter vivos – It means during the lifetime. Thus a wakf is created during the lifetime of the wakif and takes effect from that very time.

- By will– It stands in contradiction with the wakf. It takes effect after the death of the wakif and also called testamentary wakf. A wakf by will cannot operate upon more than one-third of net assets, without the consent of the heirs.

- During death illness (Marz-ul-maut) – The wakf made during the deadly illness will operate only to the extent of one-third of the property without the consent of the heirs of the wakif.

- By immemorial user – wakf may be established by evidence of immemorial user. For e.g. when a land has been from time immemorial use for the purpose of a burial ground, it is a wakf by the immemorial user.

Statutory control over Wakfs – The Wakf Act, 1995

It is no longer a secret that the most of the religious institutions are badly managed and bad management of wakf with regards to their funds and abuse of the setup have reached menacing proportions.

The Government of India being aware of this state of affairs passed the Wakf Act, 1923. During the British rule, several provinces passed statutes to control the management of religious institutions. Some of these applied to wakf also. But things did not improve. The Wakf Act, 1923 was replaced by Wakfs Act, 1954, which was amended in 1964. But things still did not improve much. Parliament then passed the Wakf Act, 1995 for the better administration of wakfs and connected matters thereof.

The Act provides for the survey of all wakfs and registration of wakfs. A Central Wakf Council is stipulated to be established for overseeing, advising and looking after the working of Wakf Boards. The Act is also stipulated to establish Wakf Boards in each state, if necessary, separate Wakf Board of Shia and Sunni Wakfs. The Wakf Board is the main instrumentality for the management of Wakfs.

Registration of Wakfs (Section 36, The Wakf Act, 1995)

The Act makes registration of every wakf compulsory. Mutawallis of wakfs are required to move an application for registration of wakfs. Such an application can also be made by a wakf or his descendants or a beneficiary of a wakf. The application should state the following particulars:

- a description of the wakf properties sufficient for the identification thereof;

- the gross annual income from such properties;

- the amount of land revenue, cesses, rates and taxes annually payable in respect of the wakf properties;

- an estimate of the expenses annually incurred in the realisation of the income of the wakf properties;

- the amount set apart under the wakf for—

-

- the salary of the mutawalli and allowances to the individuals;

- purely religious purposes;

- charitable purposes; and

- any other purposes;

- any other particulars provided by the Board by regulations.

The Board may require the applicant to supply any further particulars or information that it may consider necessary.

On receipt of an application for registration, the Board may, before the registration of the wakf make such inquiries as it thinks fit in respect of the genuineness and validity of the application and correctness of any particulars therein and when the application is made by any person other than the person administering the wakf property, the Board shall, before registering the wakf, give notice of the application to the person administering the wakf property and shall hear him if he desires to be heard.

In the case of wakfs created before the commencement of this Act, every application for registration shall be made, within three months from such commencement and in the case of wakfs created after such commencement, within three months from the date of the creation of the wakf: Provided that where there is no board at the time of the creation of a wakf, such application will be made within three months from the date of establishment of the Board.

References:

- Aqil Ahmad, Mohammedan Law, 23rd Edition

- Dr. Paras Diwan, Muslim law in Modern India, 12th Edition

- M. Hidayatullah, Mulla Principle of Mohammedan Law,19th Edition

- SCC Online

Mayank Shekhar

Mayank is an alumnus of the prestigious Faculty of Law, Delhi University. Under his leadership, Legal Bites has been researching and developing resources through blogging, educational resources, competitions, and seminars.